A Table-Driven Test Template for Elixir

The Template Itself

If you need to copy-paste:

for {name, params} <- %{

"test name 1" => %{},

"test name 2" => %{},

"test name 3" => %{}

} do

@tag params: params

test name, %{params: params} do

# use params.??? throughout

end

end

Bonus: no library or extra framework.

How It Works?

It’s easy to miss, but the ExUnit documentation mentions @tag

By tagging a test, the tag value can be accessed in the context, allowing the developer to customize the test.

Yes: anything after @tag is automatically merged into the test’s context. 🔥

Why?

Imagine some simple tests. The code itself doesn’t matter, so let’s use something trivial on purpose.

test "simplest case" do

assert MyMath.add(1, 1) == 2

end

test "normal case" do

assert MyMath.add(3, 4) == 7

end

test "mixed signs" do

assert MyMath.add(-2, 4) == 2

end

This isn’t the worst test code out there. But things start to take a bad turn when:

- tests are long

- the difference between tests is subtle (forcing you to play spot 7 differences)

- you are willing to copy-paste just another test

- you feel like giving up on testing

The real core of the test code is this:

test "___" do

assert MyMath.add(___, ___) == ___

end

Everything else is noise. That includes the values themselves, which are often arbitrary, see property-based testing.

The Journey

But how do we wrap our test “core” in a for-loop, then?

First, the wrong way:

# this is NOT going to work...

for {name, a, b, res} <- [

{"simplest case", 1, 1, 2},

{"normal case", 3, 4, 7},

{"mixed signs", -2, 4, 2}

] do

test name do

assert MyMath.add(a, b) == res

end

end

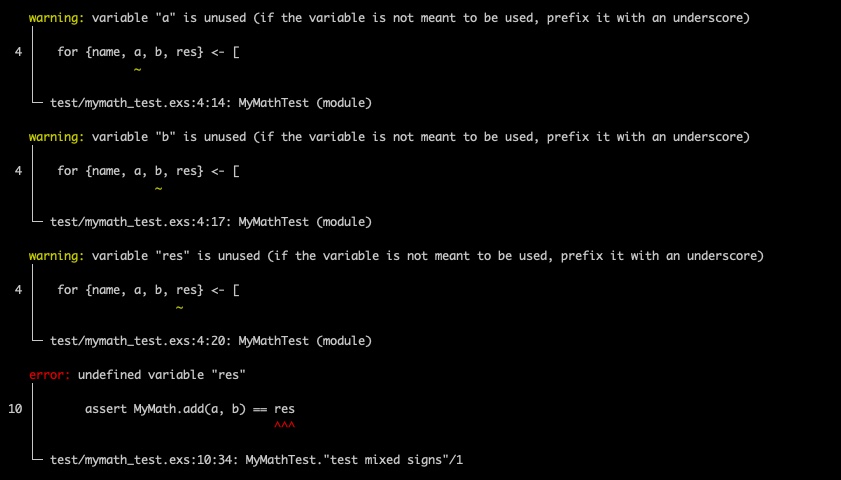

Nothing works. For example, we get both res is unused AND undefined variable res !

Long story short: compile-time versus runtime. Putting name after the test macro is OK. But using a, b or res inside the test won’t work.

There are solutions involving unquote, but I found those unpleasant and brittle (they have edge cases). Let’s skip macro magic.

for {name, a, b, res} <- [

{"simplest case", 1, 1, 2},

{"normal case", 3, 4, 7},

{"mixed signs", -2, 4, 2}

] do

@tag params: %{a: a, b: b, res: res}

test name, %{params: params} do

assert MyMath.add(params.a, params.b) == params.res

end

end

Over time, I found a recipe, with better labelling, that I’m happy with:

for {name, params} <- %{

"simplest case" => %{a: 1, b: 1, res: 2},

"normal case" => %{a: 3, b: 4, res: 7},

"mixed signs" => %{a: -2, b: 4, res: 2}

} do

@tag params: params

test name, %{params: params} do

assert MyMath.add(params.a, params.b) == params.res

end

end

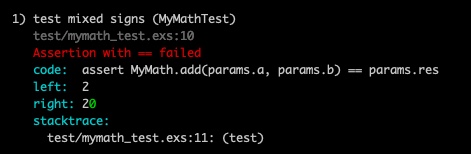

And here’s how it looks when it fails:

Why? (round 2)

You can read more about table-driven tests elsewhere. Although I would start with Prefer table driven tests.

I would summarize:

- reduce duplication

- reduce boilerplate

Both of these properties lead to higher information density per line of code.

In the template above, all cases are grouped together. That makes it easy to review, compare, and add new cases.